Is the TPLO really the best fit for my dog’s knee injury?

So your dog has been having difficulty using his hindlimb and you went to your primary care veterinarian and she said that your dog has a ligament injury, called cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) disease. She said that your dog likely won’t do well without surgery. She suggested, in particular, the TPLO. And then your veterinarian said, by the way, this will probably happen in your dogs other leg in the next few months to years. You’ve been told by your neighbor that the surgery is expensive. So what is the deal? Is this really the case? Is surgery legitimate? Is this a scam? Another way for veterinarians to make money?

Well, let’s take a moment to discuss the myth that veterinarians are just out to make money. Um, no. We pride ourselves on practicing the best medicine while getting full value for your dollar. As a profession, we are quite frugal with our money and your money. Honestly, we are the hardest type for accountants and bookkeepers to manage because we often do not charge for services as we should. We value your money as we value our own. However, there is a cost to excellent veterinary care. We chose to do graduate school (and in many cases take on tremendous debt) in order to dedicate our lives to better your pet’s life. We do so happily, but there is cost to providing our expertise, state of the art equipment, advanced medical treatments and surgeries, boarding, medications, staffing in order to give your pet the longest, healthiest life possible.

But back to the TPLO question….

Pets have similar anatomy to the knee joint as humans. There is a cranial (anterior) cruciate ligament and caudal (posterior) cruciate ligament that criss-cross, thus the name. The cranial cruciate ligament provides stability to the joint in a forward to backward plane and prevents internal rotation as well. The caudal cruciate ligament provides fairly minimal stability, helping some in full flexion of the knee. There are medial and collateral ligaments that lend additional support.

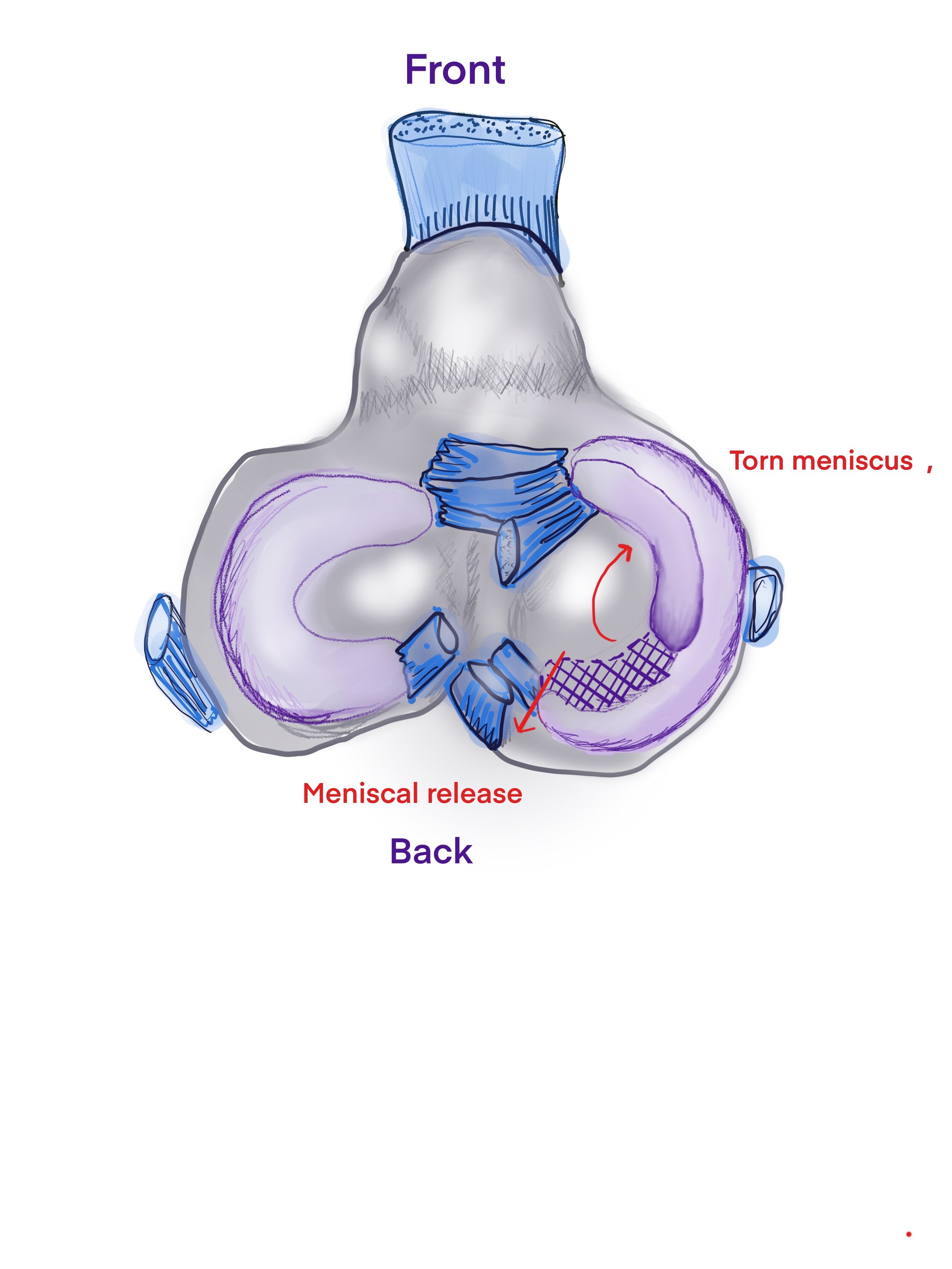

Aerial view of the top of the tibia

The purple c-shaped structures are the medial and lateral menisci. They are shock absorbers and cushions of the joint. They allow the round bottom end of the femur fit better with the flat top of the tibia. They distribute the stress of impact with each hop, step and jump.

When dogs injure their CCL, it is typically a wear and tear, slow degenerative process unlike the sudden injury of someone skiing or playing football. In dogs, the cruciate ligament is like a braided rope and it starts to fray and pop with repetitive micro trauma such as launching off the porch or couch, or chasing a ball or frisbee. A subtle intermittent lameness may be noted off and on in the early stages. Typically this progresses to a more severe, debilitating lameness. The landing and twisting of frisbee and ball is one of the hardest motions on a dog’s knee. Bad news, I know.

Torn Cranial Cruciate ligament

The cruciate ligament can be partially or completely torn. Dogs can have a severe lameness with a partial tear. An important note is all partial tears will become complete tears. Once the tearing starts it cannot be repaired or reversed. It is for this reason, that surgery is recommended once pathology is noted because this irreversible injury is best treated early in the process to minimize the progression of long term arthritis. The longer the knee is unstable the worse arthritis will be. This does not make this injury an emergency but rather it should ideally not be put off for several months.

Once the CCL is injured, lameness ensues. When the CCL tears, the tibial (shin bone) is able to slide forward relative to the femur (thigh bone), resulting in cranial drawer motion. This instability along with the inflammation of the CCL tear set the scene for lameness and arthritis. Lameness can be mild or non-weightbearing. In addition to the tearing of the CCL, the menisci can be damaged. Most typically the caudal (back) aspect of the medial (inside) meniscus is injured. This can make many dogs not want to use the affected leg at all. If severe, you can sometimes hear a clicking when they walk.

Unfortunately most pets will not do well long term without surgical stabilization. We used to say that smaller dogs can do well without surgery or inactive dogs. Sadly, if your dog uses his legs that he or she will benefit from surgery. No surgery means more advanced arthritis, pain and inflammation. Muscles will atrophy (thin out) and the knees with thicken with scar tissue. Dogs with chronic CCL injury will shift their weight in to their forelimbs putting excessive pressure on elbow, shoulder and carpal (wrist) joints. This gives dogs the classic “bull dog look.” This can agitate previously mild arthritic conditions of the forelimbs and lead to muscle strains. Over time, dogs will become less active and just seem old.

On the other hand, with surgical stabilization, pets will feel better, use their legs well and maintain or return to active lives. Although surgery does not stop or reverse arthritis, stabilization lessens the amount of arthritis that will develop lifelong. Muscle will return to full strength and comfort returns. There are several options for surgical stabilization.

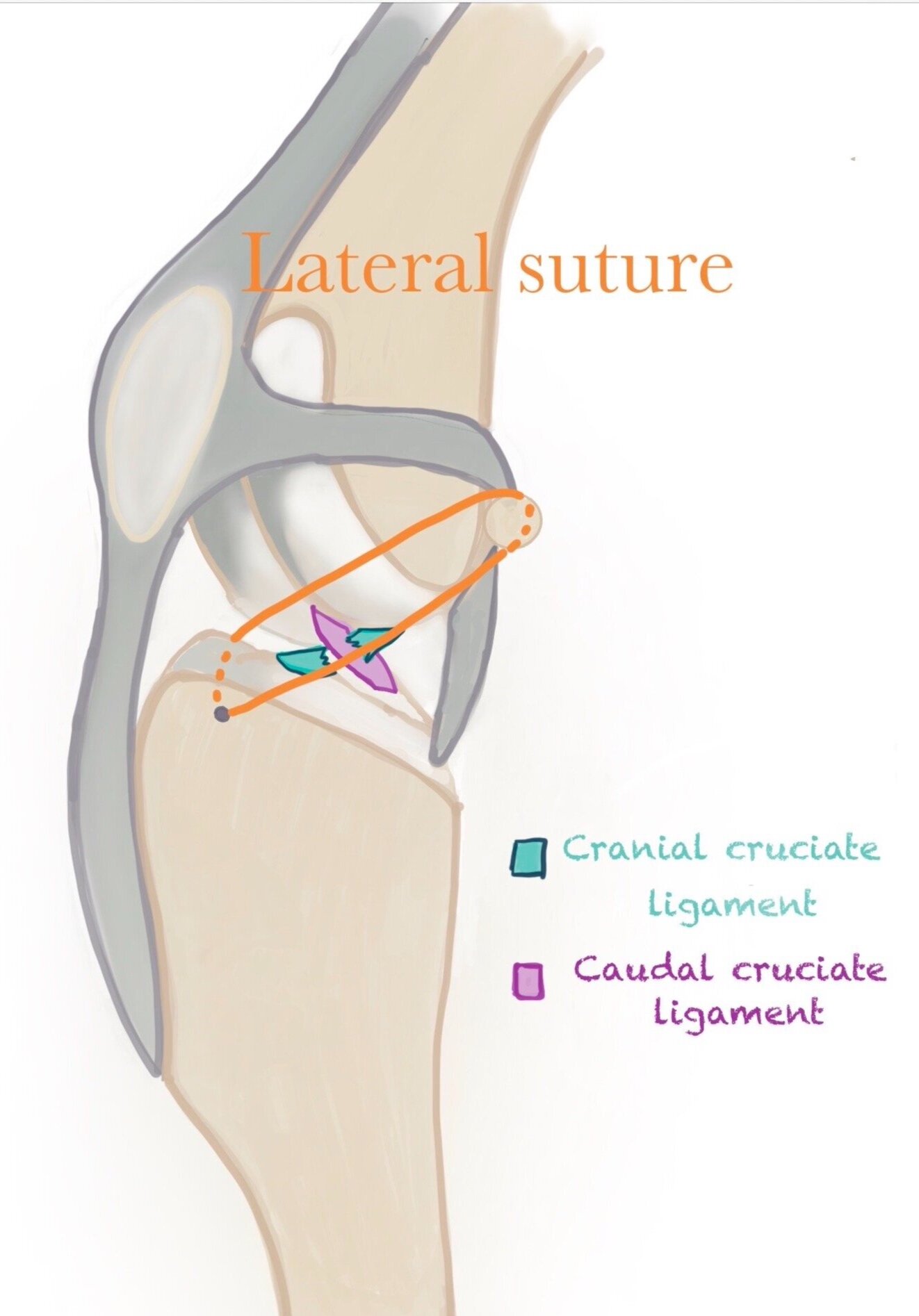

The extra capsular lateral suture stabilization (ELSS) aka medial retinacular imbrication technique, and “the band” technique was the original repair used in veterinary medicine. This technique uses a heavy, non absorbable suture material that acts as the scaffold for scar tissue. The idea is if scar tissue forms reliably then when the suture material weakens (months to years later), the scar tissue should stay tight and provide stability. Problems arise when pets are too active after surgery and stretch out the scar tissue, never providing a stable knee. Additionally, scar tissue is unpredictable and not as strong as the original CCL. This can lead to a lame dog and understandably upset owners.

Although the lateral suture has a limited role (small, compromised dogs financially constrained owners) other techniques such as the TPLO and TTA are much more reliable, predictable, provide almost normal outcomes (95%) and honestly, are less stressful during the recovery.

My preference of the current knee stabilization techniques is the TPLO. TPLO stands for tibial plateau leveling osteotomy. There are many advantages to the TPLO. The TPLO changes the biomechanics of the knee via a controlled fracture, using the dog’s own ligaments for stabilization.

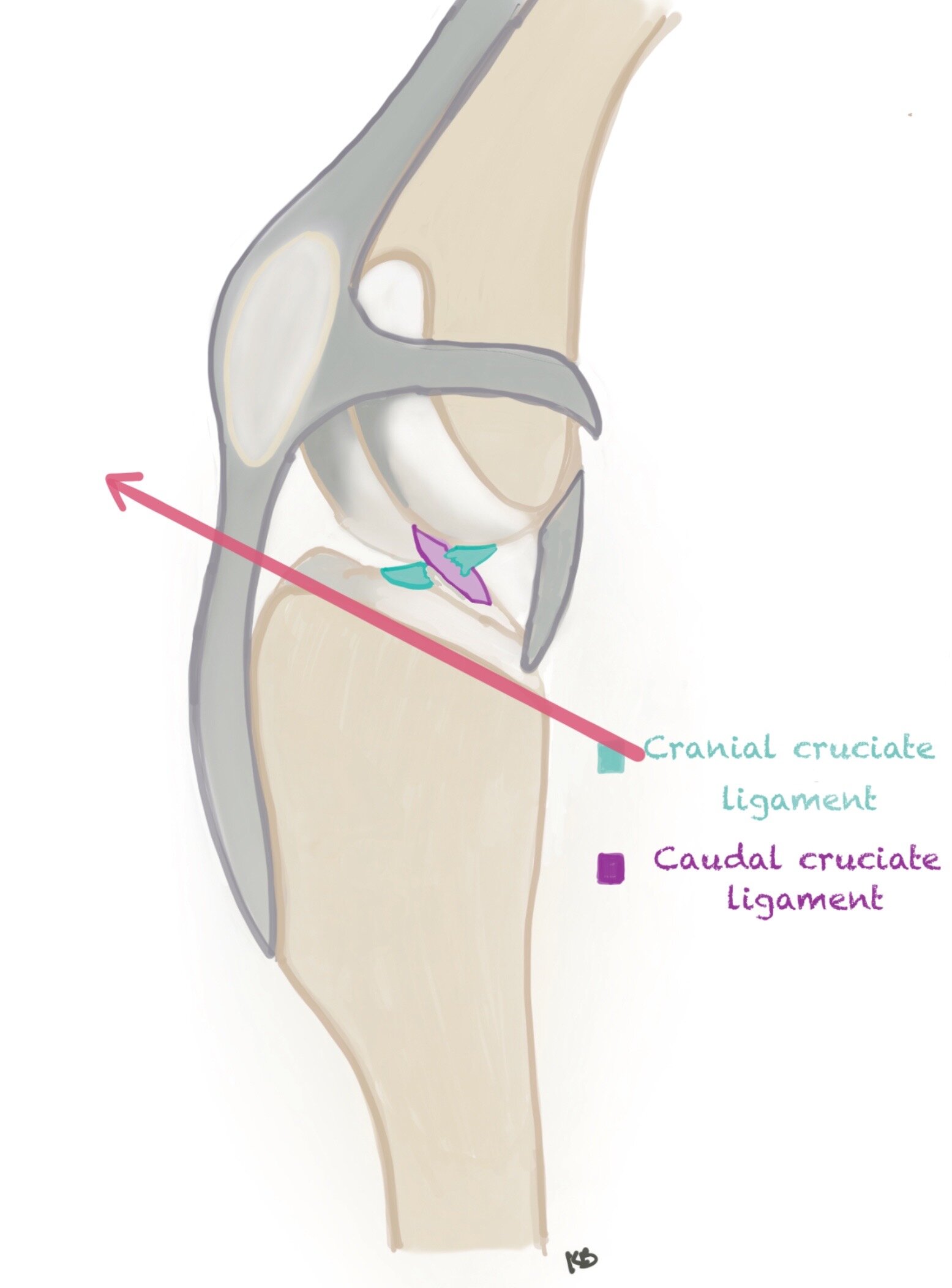

TIBIAL SLOPE

The TPLO is based on the fact that the top of the tibia, or tibial plateau, has an upward angle in all dogs (and cats). This angle is measured with anatomically perfectly positioned radiographs (x-rays) in order to accurately plan for surgery.

The average dog has a slope of 25 to 40 degrees up from normal (flat, 0 degrees).

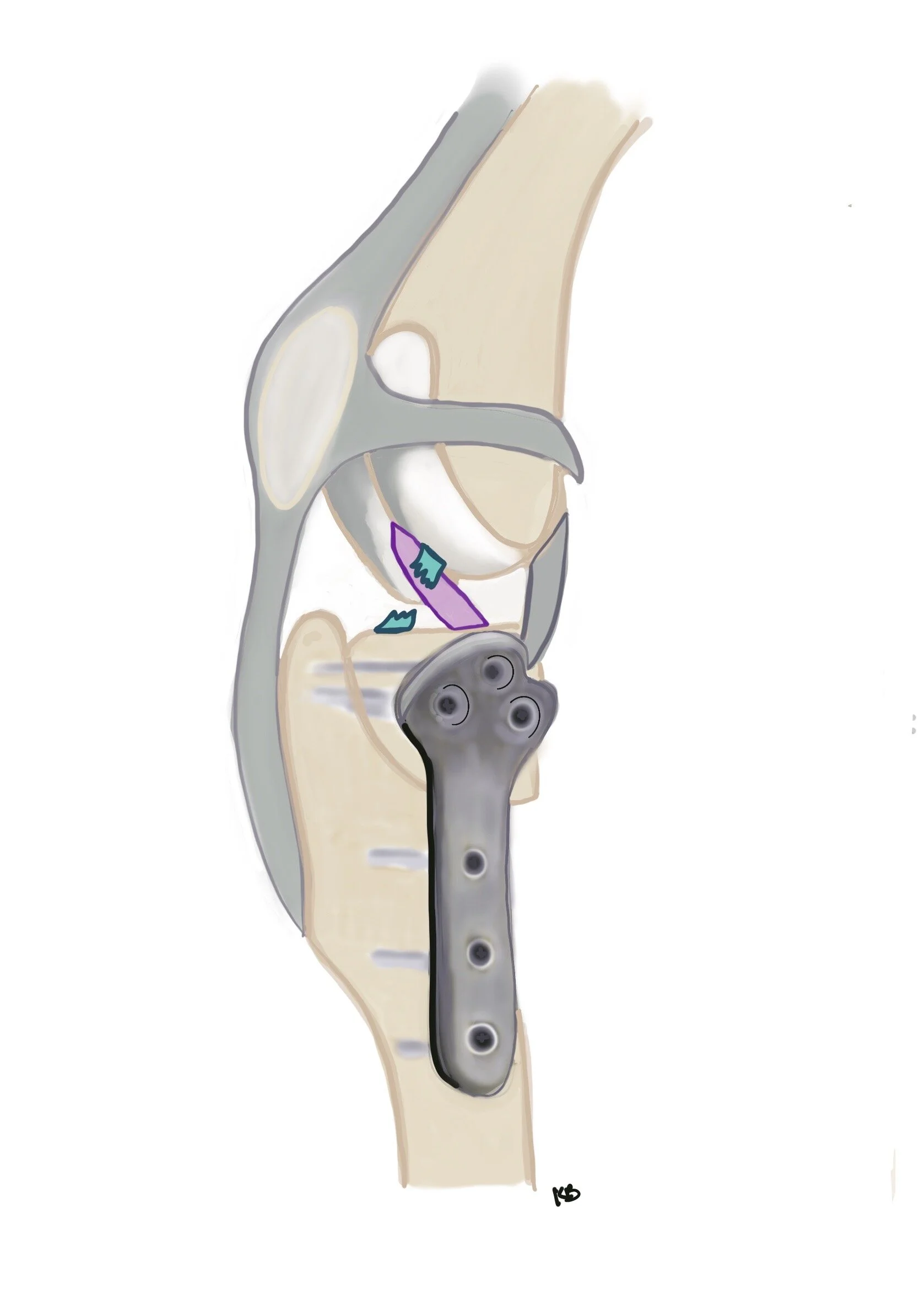

The osteotomy or bone cut

A bone cut is made, full thickness through the bone at the top of the tibia. This small portion of bone is rotated to the proper position (based on tibial slope measurement, see above).

The proximal bone piece (top small portion) is rotated to the optimal position. This position puts the CAUDAL cruciate ligament under tension making it the primary stabilizer of the knee. The ruptured CRANIAL cruciate ligament is no longer necessary. Good news is your dog won’t know the difference and neither will you, judging from the exterior. The general knee appearance remains the same.

The osteotomy (bone cut) is essentially a controlled fracture that is held in the new optimal position with a bone plate. Unlike scar tissue, bone will heal to 100% in a predictable time frame of 8 to 12 weeks. Another advantage is this repair is quite sturdy. Thanks to bone implant technology, this repair can handle much more wear and tear than the lateral suture technique. Having said this, leash control is necessary for 10 weeks.

Don’t forget the meniscus!

While in surgery, partial or complete rupture of the CCL will be documented. The meniscus will also be inspected. The medial meniscus has the highest propensity for tearing especially with complete CCL tears. This is due to instability experienced by the joint that is taken on by the meniscus. Given its specific anatomy, the medial meniscus gets hit the hardest by the sliding of the tibial relative to the femur.

Meniscal tears

The tear in the meniscus cannot be repaired due to poor blood supply, rather the torn portion is removed and the rest is preserved. The removal of a tear brings major relief to the joint and thus your dog. Tears can also come in delay of stabilization requiring additional surgery. Alternatively, a meniscal release may be performed at the surgeon’s preference.

And of course with every surgery comes potential complications. Luckily with the TPLO in the hands of a qualified surgeon, major complications are rare and minor complications are manageable and recoverable. Patella tendonitis, infection, fractures, delayed meniscal tears top the list.

Patella tendonitis or patella tendon thickening

Along with the caudal cruciate ligament taking on a new role as the primary joint stabilizer, the patella tendon also takes on new strain. Temporarily this can result in thickening of the tendon. In some dogs this is noted by a persistent lameness that requires additional rest and anti-inflammatories. Some dogs show no signs of lameness from the thickening. Yet others will not have visible thickening at all. This can be noted at the 10 week recheck and will be addressed accordingly. The condition is completely recoverable and the long term outcome is not altered for the worse.

Infections

Most infections start as superficial infections are the result of incision licking. Evidence of licking includes missing sutures, saliva staining and imperfect wound edges (see picture). A lack of timely healing with risk of superficial infection noted at the two week recheck or earlier, may warrant additional time in the e-collar and extended antibiotics beyond the prophylactic course provided at discharge. The cone/e-collar or other wound coverage such as surgical sleeves is essential for minimizing the risk of infection. The risk of superficial infection is approximately 5 to 10%.

Deep Infection:

Less than 2 to 5% of cases will develop a deep infection. This typically occurs when a dog licks the incision and the infection progresses to deep tissues. In these cases, a culture is taken and submitted to the lab. Once the organism is known the proper antibiotic can be given to heal the infection and heal the bone. Unfortunately, long term, bacteria can hide in the implants (protected by a biofilm) and so once the bone has healed, the plate must be removed. Luckily at that point, the plate is not longer necessary and is NOT REPLACED. This is a big benefit of the TPLO. Most dogs, however, will keep their bone plates lifelong.

Draining Tract:

A wound that develops weeks to months after your dog’s TPLO is typically an indication for plate removal due to a lingering implant infection. This can occur weeks to years after surgery.

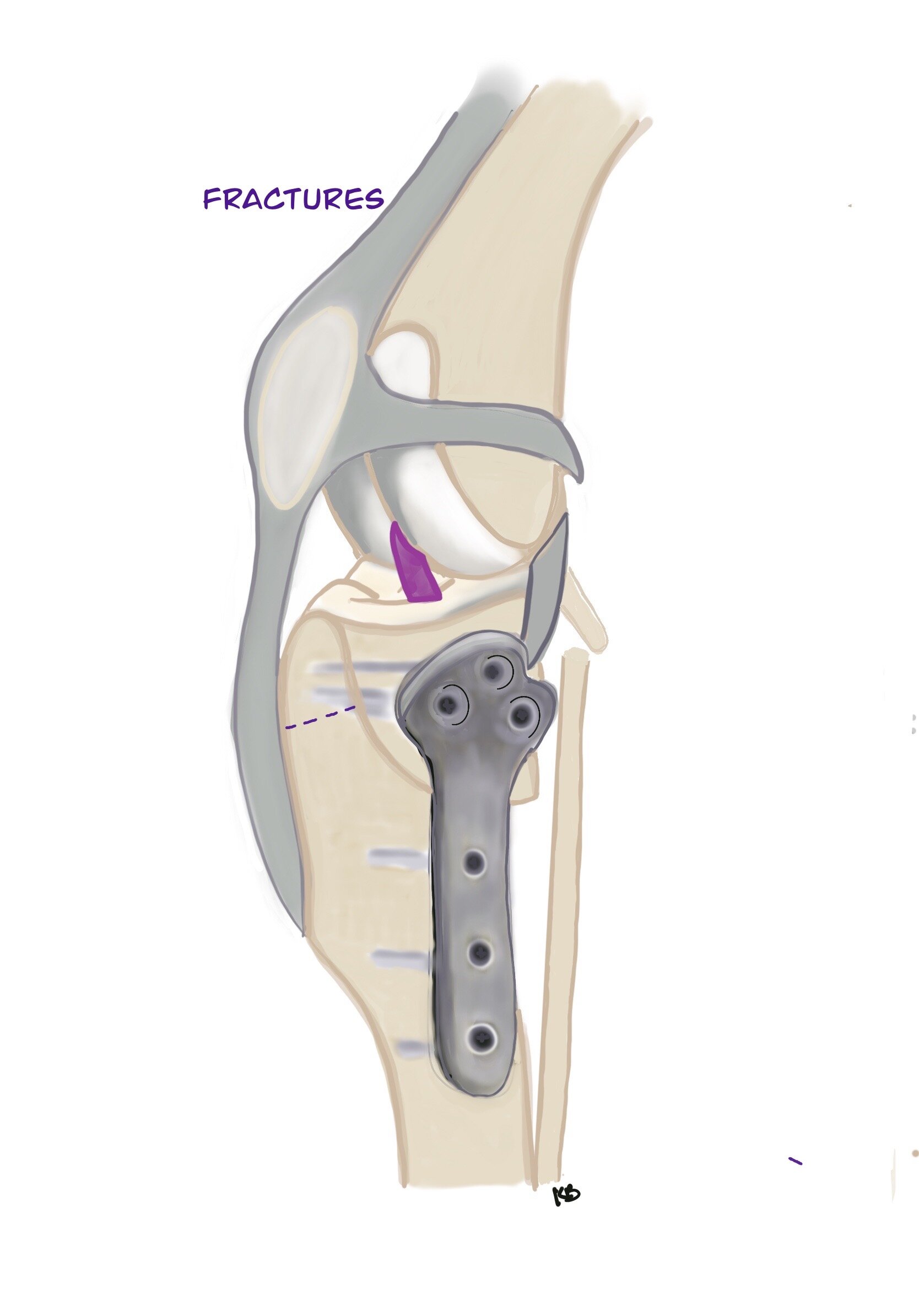

Fractures

Fractures can occur secondary to the TPLO procedure. A fracure of the small skinny fibula bone (2%) is not a serious complication and does not require additional surgery. It is not a weight bearing bone and it will heal on its own. A fracture of the tibial crest is quite rare (1%) and in some cases requires additional surgery to pin the fracture back in place if movement of the fractured piece is noted. The chances of this happening are reportedly increased with bilateral procedures

Delayed Meniscal Tears

As mentioned earlier, meniscal tears can occur. Rarely, <10% of cases will develop a delayed tear, months to years after stabilization surgery. This does require additional surgery to remove the meniscal tear.

The recovery period is approximately 10 weeks. During this time, your dog must be on leash when outside. Only low impact activity is allowed. No running, jumping, or rough-housing. Minimal stairs are allowed. Several stairs to go outside is ok if on a leash and going slowly. Going up and down full flights indoors is best avoided. A crate is typically the best option if your dog is crate trained. If your dog is not crate trained, the small room without objects to jump on can be a good fit e.g. mud room, laundry room, or X-pen. We want your dog to use its leg, but use it gently. Walks for the first month will be limited to the yard and then afterwards slowly extended over 10 weeks to reach 25 minutes. At the 10-week mark, recheck radiographs will be taken to see if bone healing has occurred. During this period we are rehabbing the surgery leg as well as trying not to over do it on the non-surgical leg. Please ask any questions at your consultation, we are here to help!!